Missing link in Indo-European languages’ history found — New insights into our linguistic roots via ancient DNA analysis

Where lies the origin of the Indo-European language family? This question is being investigated by the international research team that, over the past few years, has analysed the DNA of 435 prehistoric individuals from more than one hundred archaeological sites across Eurasia between 6400 and 2000 BC. Their study, published in Nature on 5 February 2025, provides new findings that bring us closer to answering this 200-year-old question. They report that a newly recognized Caucasus-Lower Volga population can be connected to all Indo-European-speaking populations.

A team of researchers led by Iosif Lazaridis, Nick Patterson, and David Reich at Harvard University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Ron Pinhasi at the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology and Human Evolution and Archaeological Sciences (HEAS) at the University of Vienna; David Anthony at Hartwick College, Department of Anthropology Oneonta; and Leonid Vyazov at the University of Ostrava, Czech Republic—together with 128 co-authors—contributed to addressing this question. Hungarian researchers were also involved in the study through archaeological, physical anthropological, and archaeogenomic analyses of prehistoric communities from the territory of present-day Hungary. Specialists from the HUN-REN Institute of Archaeogenomics and the Institute of Archaeology, the Department of Biological Anthropology at Eötvös Loránd University, the Department of Anthropology at the University of Szeged, the Déri Museum in Debrecen, the Damjanich János Museum in Szolnok, and the Department of Anthropology of the Hungarian Natural History Museum participated in this work.

A burial mound (kurgan) associated with the former Yamnaya culture in the boundary of Hajdúnánás (Hajdúnánás-Fekete-halom; Photo: János Beregszászi)

The first results of the study, submitted in April 2024, were presented at the “Transformation of Europe in the Third Millennium BC” conference held at the HUN-REN Institute of Archaeology. The two first authors of the paper, David Anthony and David Reich, introduced the preliminary findings. The recorded presentations are available on the HUN-REN RCH YouTube channel.

Indo-European languages (IE), which number over 400 and include major groups such as Germanic, Romance, Slavic, Indo-Iranian, and Celtic, are spoken by nearly half the world’s population today. Originating from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language, historians and linguists since the 19th century have been investigating its origins and spread as there is still a knowledge gap

The new study published in Nature analyzes ancient DNA from 435 individuals from archaeological sites across Eurasia between 6400-2000 BC. Earlier genetic studies had shown that the Yamnaya culture (3300-2600 BC) of the Pontic-Caspian steppes north of the Black and Caspian Seas expanded into both Europe and Central Asia beginning about 3100 BC, accounting for the appearance of “steppe ancestry” in human populations across Eurasia 3100-1500 BC. As a result of this expansion, burials beneath the characteristic mounds, or so-called kurgans, appeared in large numbers on the Hungarian Plain. This process seems to have occurred in several waves, during which smaller or larger groups likely broke away from the nomadic Yamnaya communities of the Eurasian steppe, seeking new pastures toward the Balkans, the Carpathian Basin, and Inner Asia.

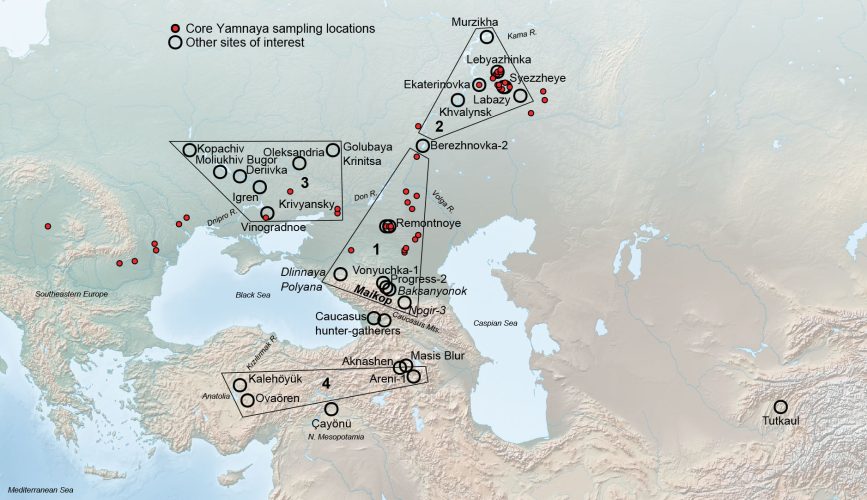

Based on the results of the present study, three genetic transitions (so-called gradients) have been identified in Eastern Europe and Southwest Asia during the 5th–4th millennia BC:

- The first, the Caucasus–Lower Volga gradient, in which the genetic heritage of Caucasian hunter–gatherer populations predominated. This gradient extends from the Caucasus region as far as the Berezhnovka site along the Lower Volga. Bidirectional gene flow created transitional populations, as observed, for example, in the populations of the North Caucasian Maikop culture and the Remontnoje site on the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

- The second, the Volga gradient, emerged from the admixture of the Caucasus–Lower Volga populations with Upper Volga hunter–gatherer populations of Eastern European origin, producing highly diverse groups.

- The third, the Dnieper gradient, arose from the mixing of westward-moving Caucasus–Lower Volga communities with Neolithic hunter–gatherer populations along the northern Black Sea coast, occurring along the Dnieper River. Archaeologically, this can be associated with the Serednii Stih cultural groups. According to the genetic results, these populations directly contributed to the core population of the later Yamnaya phenomenon around 4000 BC, which underwent rapid population growth between c. 3750–3350 BC and subsequently expanded, aided by favourable climatic and environmental conditions.

Genetic analysis of pre-Bronze Age populations in the Pontic–Caspian Steppe and Western Asia highlights four key regions. The red dots indicate Yamnaya culture sites from which samples belonging to the genetically defined central Yamnaya group were obtained.

These migrations out of the steppes had the largest effect on European human genomes of any demographic event in the last 5000 years. Although language and genetic ancestry do not always align perfectly, it is likely that this population movement can be regarded as the probable vector for the spread of Indo-European languages.

The spread of the Yamnaya phenomenon across Eurasia around the turn of the 4th–3rd millennium BC (Trautmann et al. 2023, Fig. 1)

The only branch of Indo-European language (IE) that had not exhibited any steppe ancestry previously was Anatolian, including Hittite, probably the oldest branch to split away, uniquely preserving linguistic archaisms that were lost in all other IE branches. Previous studies had not found steppe ancestry among the Hittites because, the new paper argues, the Anatolian languages were descended from a language spoken by a group that had not been adequately described before, an Eneolithic population dated 4500-3500 BC in the steppes between the North Caucasus Mountains and the lower Volga. When the genetics of this newly recognized Caucasus-Lower Volga (CLV) population are used as a source, at least five individuals in Anatolia dated before or during the Hittite era show CLV ancestry. Recognition of this connection may represent the missing link that genetically—and, by extension, linguistically—connects communities living in the North Caucasus–Lower Volga steppe region during the Eneolithic period (c. 4500–3500 BC) with those in Anatolia before or during the Hittite period.

The missing link — Newly recognized population with broad influence

The new study shows the Yamnaya population to have derived about 80% of its ancestry from the CLV group, which also provided at least one-tenth of the ancestry of Bronze Age central Anatolians, speakers of Hittite. The CLV group therefore can be connected to all IE-speaking populations and is the best candidate for the population that spoke Indo-Anatolian, the ancestor of both Hittite and all later IE languages, in the North Caucasus and Lower Volga region between 4400 BC and 4000 BC.

The significance of Carpathian Basin data in the research

The genetic samples from Hungary analysed in the study come from the westernmost extent of the Yamnaya communities’ distribution, namely from burials under the mounds (kurgans) of the Hungarian Plain in the Carpathian Basin, appearing around the turn of the 4th/3rd millennium BC. These sites—Dévaványa, Kunhegyes, Nagyhegyes, Sárrétudvari, and Mezőcsát—have been excavated over the past decades. The new results confirm the Eastern European genetic connections of these individuals. From an earlier period, around 4200 BC, a remarkable burial from the Csongrád-Kettőshalom site was analysed. The male interred there is one of the earliest individuals in the Carpathian Basin with genetically confirmed steppe ancestry, and a close relative of his has also been identified along the Volga. Human DNA samples from the Hungarian sites were processed partly at the HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archaeogenomics, and partly at the universities of Vienna and Harvard. Further archaeological, linguistic, anthropological, and archaeogenomic results are expected in the near future from the communities under study, as part of the ERC Yamnaya Impact project and the long-term international research collaborations initiated in 2015 focusing on Bronze Age individuals across the broader Carpathian Basin.

Work at the HUN-REN RCH AGI laboratory, where part of the samples was processed.

The study can be accessed here:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-08531-5

Hungarian researchers and institutions involved in the study:

HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archeogenomics

Anna Szécsényi-Nagy

HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archaeology

Gabriella Kulcsár, Viktória Kiss, Eszter Melis

ELTE Faculty of Science, Department of Biological Anthropology

Tamás Hajdu

University of Szeged, Faculty of Humanities, Institute of Archaeology/ Déri Museum, Debrecen

János Dani

University of Szeged, Department of Biological Anthropology

Zsolt Berecki, Erika Molnár, György Pálfi

Damjanich János Museum, Szolnok

Marietta Csányi, Judit Tárnoki

Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest

Sándor Évinger

Hungarian projects supporting the research:

MTA–BTK Lendület “Momentum” Mobility Research Group (2015–2022) és MTA–BTK Lendület “Momentum” BASES Research Group (2023–)

HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archaeology

Project funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NRDIO), grant number FK-12801

János Bolyai Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Further information:

Gabriella Kulcsár; kulcsar.gabriella@abtk.hu

Anna Szécsényi-Nagy; szecsenyi-nagy.anna@abtk.hu

János Dani; dani.janos@derimuzeum.hu

Tamás Hajdu; tamas.hajdu@ttk.elte.hu