Social organization thematic group

Recent trends in archaeology include the bioarchaeological and biosocial research of individuals and social units. In addition, the Bronze Age is a significant period in the evolution of political arrangements, with one of the most important aspects being the emergence of the chiefdom society – a marker of the institutionalisation of social inequality. A key question is what (not purely biological) bonds can be identified between the basic units of society (the members of families and clans in this period. In recent years, the results of archaeogenetics have been employed in a number of analyses of family relationships prior to the availability of written sources, including those of Bronze Age communities.

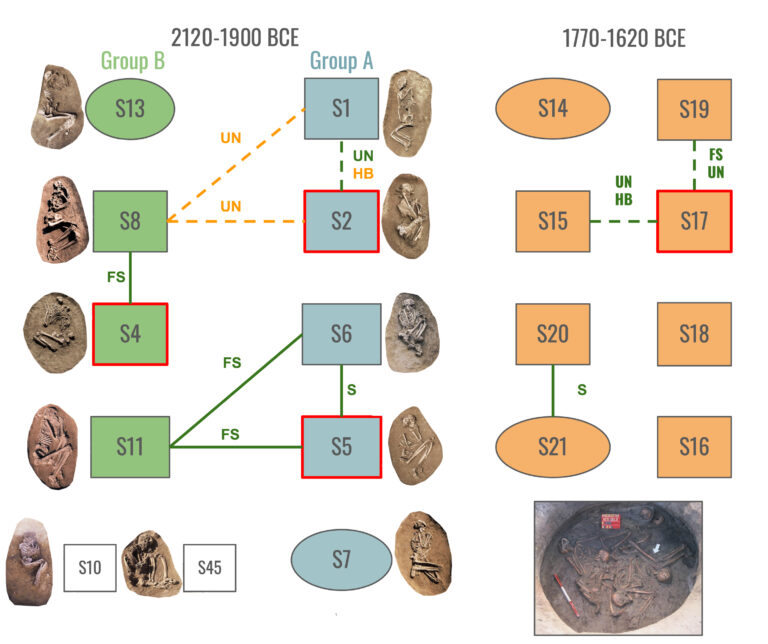

Biological kinship relationships emerging from the archaeogenetic results of Early and Middle Bronze Age burials in Balatonkeresztúr-Réti-dűlő (solid line: first-degree kinship, dotted line: second-degree kinship, green: proven, orange: possible, unconfirmed kinship relationship; FS: father-son, UN: uncle-nephew, S: siblings, HB: half-siblings; © Kiss et al. 2023b, Fig. 7)

Physical anthropology, paleopathology, molecular biology

The latest bioarchaeological studies have made it possible to research man as a social entity rather than the skeleton. In addition to the classical physical anthropological analysis (determination of the sex and age of the deceased, biological reconstruction of a given population), we investigate the differences and similarities in the general health and lifestyle of different populations at one time, by means of a systematic palaeopathological analysis of pathological lesions.

Stable isotope studies

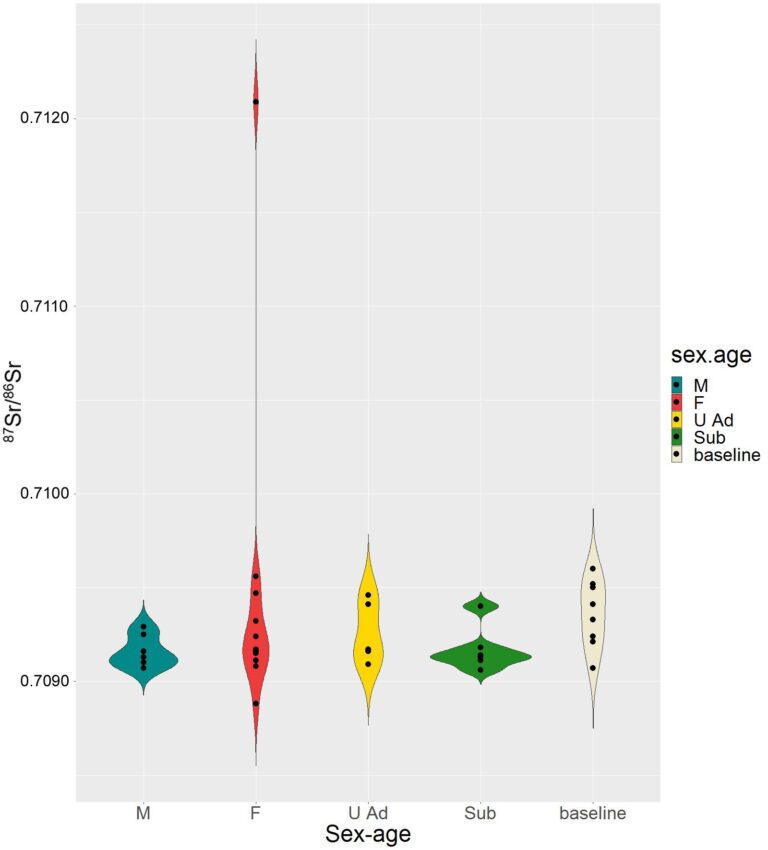

The isotopic ratios of strontium and oxygen (87Sr/86Sr, δ18O) can be detected from food and water through the food chain and from the atmosphere into the human body. The proportion of trace elements that have been permanently incorporated into the enamel of the tooth during infancy can be compared with that observed in the bone of the adult individual and in the soil of the site of discovery. This comparison can be used to determine whether there has been a significant change in location during the lifetime. The term “mobility” is more broadly understood than “migration”. It encompasses phenomena other than one-way migration, such as exogamous marriage patterns. The analysis of carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes present in the remains can provide information on the diet and lifestyle of human populations and domestic animals.

Violin plot distribution of the 87Sr/86Sr values of individuals (M=men, F=women, U Ad=adults of undeterminate sex, Sub=children) from cremation and inhumation burials compared with local baselines at Szigetszentmiklós-Ürgehegy reveal the mobility patterns characteristic of the community (© Cavazzuti et al. 2021)

Archeogenetics

The molecular genetics of Bronze Age skeletal burials has become an increasingly important and rapidly developing element of research on the mobility and ancestry of communities. The study of mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal haplotypes may provide insights into the question of whether genetically distinct populations of different origins can be identified behind Bronze Age archaeological cultures and their associated cultural phenomena. The whole-genome sequencing of aDNA samples and the implementation of targeted genomic studies have enabled the outline and further clarification of the prehistoric population history of Central Europe.

Furthermore, the integration of network analysis, behavioural and social organisation aspects into the results obtained using these methods offers the potential for biosocial archaeological analysis, thereby contributing to the understanding of early Bronze Age families/households and political structure.

The process of the facial reconstruction of a Bronze Age woman from Balatonkeresztúr (©ELTE RCH)

Our relevant works on the topic:

- Cavazzuti, C., Hajdu, T., Lugli, F., Sperduti, A., Vicze M., Horváth, A., Major, I., Molnár, M., Palcsu, L., Kiss, V.: Human mobility in a Bronze Age Vatya ‘urnfield’ and the life history of a high-status woman. PlosONE 16(7) 2021, e0254360

- Gerber, G., Szeifert, B., Székely, O., Egyed, B., Gyuris, B., Giblin, J.I., Horváth, A., Köhler, K., Kulcsár, G., Kustár, Á., Major, I., Molnár, M., Palcsu, L., Szeverényi, V., Fábián, Sz., Mende, B. G., Bondár, M., Ari, E., Kiss, V., Szécsény-Nagy, A.: Interdisciplinary Analyses of Bronze Age Communities from Western Hungary Reveal Complex Population Histories. Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 40, Issue 9, September 2023, msad182, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msad182

- Kiss, V., Czene, A., Csányi, M., Dani, J., Fábián, Sz., Fischl, K.P., Gerber, D., Giblin, J.I., Hajdu, T., Köhler, K., Melis, E., Mende, B. G., Patay, R., Szabó, G., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Szeverényi, V., Kulcsár, G.: Módszerek és lehetőségek a bronzkori közösségek kutatásában: A Lendület Mobilitás Kutatócsoport biorégészeti elemzési eredményei (2015–2020) – Methods and Opportunities in the Research of Bronze Age Communities: The Outcomes of theBioarchaeological Research Programme of the Momentum Mobility Research Group (2015–2020). Magyar Régészet – Hungarian Archaeology E-journal 10 (2021) 30–42.

- Kiss, V., Gerber, D., Fábián, Sz. Giblin, J.I., Kustár, Á., Gyuris, B., Horváth, A., Köhler, K., Kulcsár, G., Major, I., Molnár, M., Palcsu, L., Szeverényi, V., Mende, B.G., Ari, E., Szécsény-Nagy, A.: Lifeway narratives of a Bronze Age community from Balatonkeresztúr (Western Hungary) based on bioarchaeological analyses. In: Meller, H., Krause, J., Haak, W., Risch, R.: Sex, and Biological Relatedness: The contribution of archaeogenetics to the understanding of social and biological relations. 15. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 6. bis 8. Oktober 2022 in Halle (Saale). Halle (Saale) 2023, 233–248. https://doi.org/10.11588/propylaeum.1280

- Kustár, Á., Gerber, D., Fábián, Sz., Köhler, K., Mende, B.G., Szécsényi-Nagy, A., Kiss, V.: Facial reconstruction of an Early Bronze Age woman from Balatonkeresztúr (W-Hungary). Antaeus 38 (2022) 13–31.